I often hear this question from foreign friends:

“Do Japanese people eat sushi every day?”

Perhaps many of you who have visited Japan have imagined the same thing.

Beautiful sushi, marbled wagyu beef, luxurious sukiyaki… These certainly symbolize Japanese cuisine, but what Japanese people actually eat every day is very different.

The conclusion is simple: sushi and wagyu are treats, not daily food. So what do Japanese people really eat as their everyday meals? In this article, I’ll show you real examples of what young professionals cook for themselves, the home cooking I grew up with, and even some photos from my own dinner table.

— The Idea of Ichiju-Sansai —

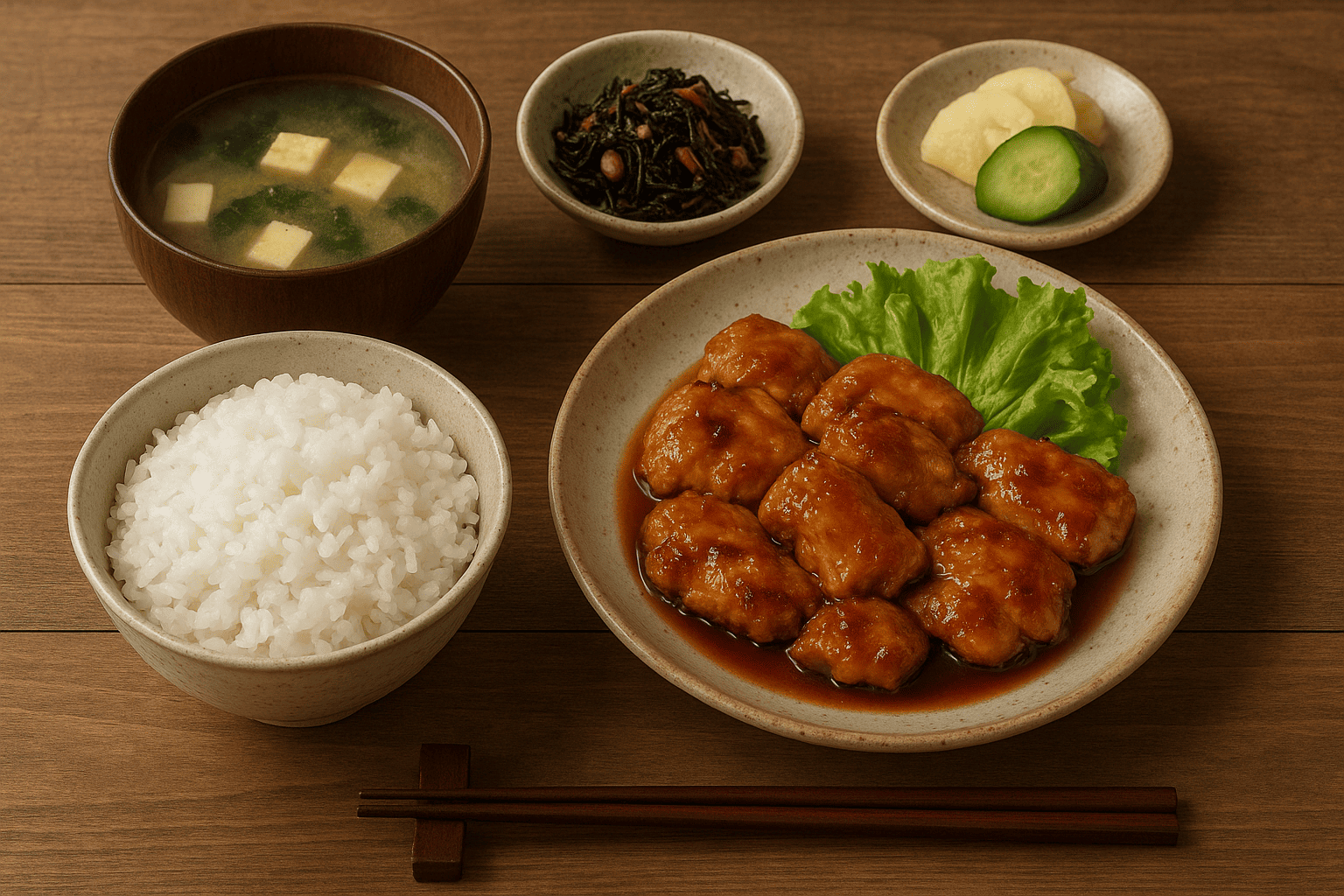

The foundation of Japanese home cooking is ichiju-sansai (one soup, three dishes). This means rice, soup, a main dish, and two side dishes. Families don’t follow it strictly every day, but “rice + soup + 2–3 dishes” is a natural pattern many keep in mind.

For example, a typical weekday dinner might be:

Steamed white rice

Miso soup (with tofu and wakame seaweed)

Teriyaki chicken

Simmered hijiki seaweed

Pickled cucumber

👀Neighbor’s Eyes

It’s not flashy, but this kind of meal is nutritionally well-balanced and represents daily life.

— Nabe: A Comfort Food That Brings People Together —

In winter, almost every family turns to nabe (hotpot). Cabbage, leeks, mushrooms, tofu, chicken or pork are simmered in a clay pot, and everyone gathers around the table.

Surprisingly, the most common hotpot in Japan is kimchi nabe. A survey ranked them as:

Kimchi (Korean-style hotpot)

Chanko nabe (soy sauce, miso, or salt flavor)

Mixed hotpot (yose-nabe)

Sukiyaki, on the other hand, is rarely an everyday dish. The reason is simple — the beef is expensive and special, so sukiyaki usually appears on birthdays or celebrations, not on ordinary nights.

In my student days, “home parties = hotpot + beer” was the rule. Friends would fight over meat and vegetables, then argue whether to finish with rice porridge or ramen — a classic scene.

Japanese supermarkets also sell countless packs of “nabe no moto” (hotpot soup bases). Just pour one into a pot, add ingredients, and you can instantly enjoy kimchi nabe, soy milk nabe, sesame miso nabe, and more. Thanks to these, hotpot has become a quick, easy, and social meal.

In my family, weekdays often meant eating separately because of busy schedules, but Sundays were different. “Since we’re all home, let’s do nabe,” someone would say, and that became our way of gathering together. Hotpot wasn’t just food — it was an event.

👀Neighbor’s Eyes

— Noodles: More Than Just Ramen —

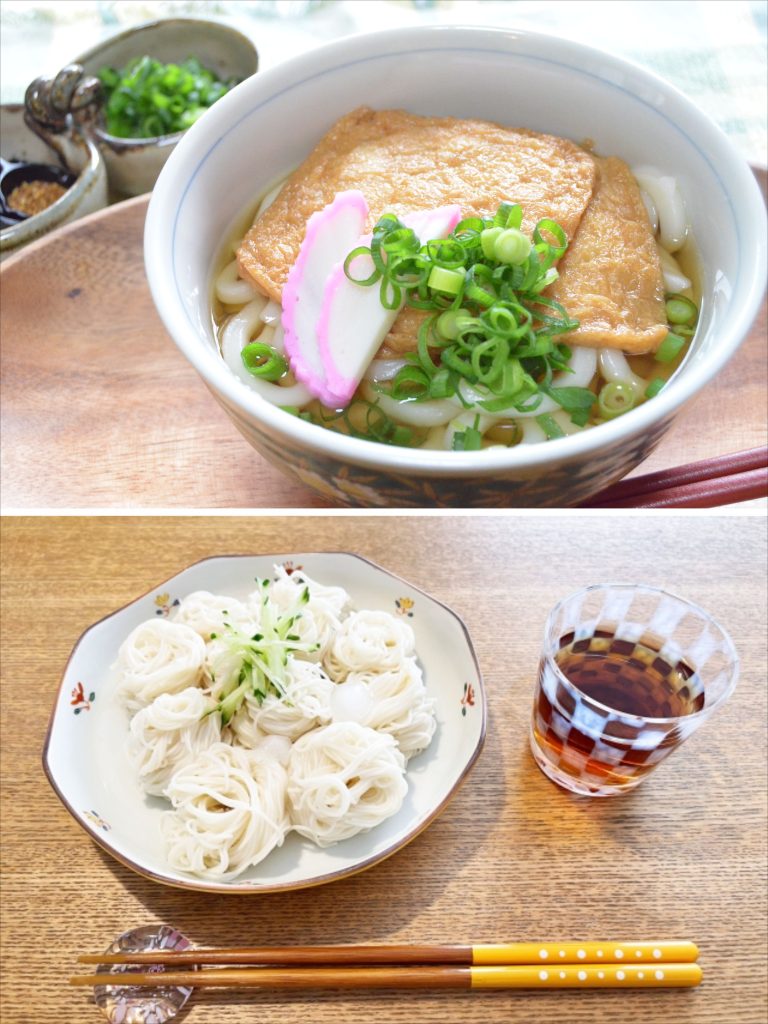

When foreigners think of Japanese noodles, ramen comes to mind first. But at home, udon and soba are far more common. The reason? Ramen takes time — broth, toppings — while udon and soba are quick, light, and easy on the stomach.

In summer: chilled soba or cold udon

In winter: hot nabeyaki udon served in a pot

On busy days: frozen udon cooked in minutes

Udon is especially convenient. Supermarkets sell powdered soup packets — just boil water, add frozen udon and soup, and lunch is ready in no time.

So while ramen shops are always popular, the reality of home cooking is simple, inexpensive, quick-to-make noodles.

👀Neighbor’s Eyes

— More Pork, Chicken, and Fish Than Beef —

One thing that surprises many foreigners is Japan’s “meat situation.”

Beef = Luxury (With Exceptions)

In Japan, beef is more expensive than pork or chicken. Wagyu, with its marbled fat, contrasts with America’s preference for lean meat. As a result, Japanese families more often eat pork, chicken, or fish.

For example:

Pork ginger stir-fry (shogayaki), Fried chicken (karaage), Grilled mackerel with salt

Pan-fried salmon, Grilled horse mackerel (aji)

These are the true everyday meals of Japanese households.

But… Gyudon Is a National Dish

There is one exception: beef bowls (gyudon).

The “big three” chains — Yoshinoya, Sukiya, and Matsuya — sell gyudon at astonishingly low prices (about ¥300–400, or $2–3). For many Japanese, gyudon represents the holy trinity of “fast, cheap, tasty.”

How can it be so cheap? Because they use “short plate,” a fatty cut of beef imported in bulk from the U.S. — unpopular there, but perfect for gyudon.

On average, Japanese people eat gyudon 10–15 times per year. Among men in their 30s, more than half go at least once a month, and about 20% go weekly. For busy students and workers, gyudon is the ultimate everyday lifesaver.

👀Neighbor’s Eyes

— Breakfast: Simple and Practical —

At hotels, tourists often see gorgeous Japanese breakfast sets. But in real homes, breakfast is much simpler.

Natto on rice + miso soup

Toast + coffee

Raw egg on rice (tamago-kake gohan)

A father quickly stirs his natto before work, a child laughs at the sticky strings, and a mother shrugs off slightly burnt toast: “It’s fine.” This practical, warm chaos is what a Japanese morning really looks like.

👀Neighbor’s Eyes

— Convenience Stores Keep Japan Running —

Modern Japan can’t exist without the convenience store. Tourists love them, but for Japanese people, they’re truly part of daily life.

Rice balls (onigiri — tuna mayo, salmon, kelp, etc.)

Sandwiches (egg salad is a staple)

Fried chicken skewers and croquettes

Packaged salads and side dishes

A common sight: a tired salaryman late at night, buying a salmon onigiri, fried chicken stick, and a can of beer before heading home.

👀Neighbor’s Eyes

Conclusion: Beyond Sushi and Wagyu

In short, Japanese people don’t eat sushi and wagyu every day. Real everyday meals are simple and balanced: pork, chicken, fish, and vegetables. And sometimes, a quick gyudon or convenience store dinner.

So when you visit Japan, don’t stop at luxury sushi or wagyu. Try a grilled fish set meal at a diner, slurp noodles at a neighborhood soba shop, or sit down with a bowl of gyudon. That’s where you’ll taste the real everyday life of Japan.

✍️ Author: Aya

Aya has traveled to over 40 countries, but always returns with love for Japan. Through Neighborly Japan, she shares a warm and authentic perspective on everyday Japanese life.

👀Neighbor’s Eyes #1

When I was a child, I sometimes grew tired of my mother’s cooking and longed for the occasional meal out. But as I got older, I found myself strangely comforted whenever simple dishes like simmered hijiki seaweed or lightly pickled cucumbers appeared on the table. They may not look glamorous, but to me, that’s the true meaning of “home cooking.”

👀Neighbor’s Eyes #2

It may surprise some to learn that kimchi hotpot only rose to the number-one spot in Japanese households over the past 30 years. Until the Showa era, the undisputed champion was yosenabe—a mixed hotpot. Back then, there were no instant soup bases. Families simply simmered kombu and fresh ingredients to create a natural broth, then dipped everything into ponzu sauce. This style, closer to mizutaki, was the norm. Even traditions evolve, and hotpot culture is no exception.

👀Neighbor’s Eyes #3

On a sweltering summer day, when your appetite seems to vanish, there’s nothing quite like chilled sōmen noodles served over ice. Topped with refreshing flavors—shiso, myoga, a touch of ginger—they slide down effortlessly. One bite leads to another, and before you know it, the bowl is gone. Scenes like this aren’t rare—they’re simply everyday Japan. Travelers can easily experience it too at a soba shop or a humble diner.

👀Neighbor’s Eyes #4

During my student days, the beef dish closest to my heart wasn’t fancy sukiyaki but the humble gyūdon. I still remember rushing into Yoshinoya late at night with friends, piling on pickled ginger, and savoring that steaming beef bowl. It’s a flavor etched into memory—and all for less than the price of a single coin.

👀Neighbor’s Eyes #5

There’s something about breakfast that reveals the unvarnished face of family life: laughing at the sticky threads of natto, or eating burnt toast with a shrug and a smile. These little moments say more about “home” than any elaborate meal.

👀Neighbor’s Eyes #6

On the way home after a long day of overtime, nothing feels better than grabbing a salmon rice ball, a fried chicken skewer, and a can of beer from the convenience store. Somehow, that’s enough to make you breathe easier. In Japan, the konbini is far more than just a shop—it’s a refuge for the busy and the tired.